A groundbreaking study confirms that large, intact fat particles are not harmless as previously thought, but actively drive inflammation and atherosclerosis in mice.

For decades, dogma held that only small cholesterol remnants could infiltrate arteries. Now, a paradigm-shifting discovery fundamentally changes our understanding of cardiovascular risk. New research reveals that large, unprocessed fat particles directly trigger vascular inflammation and drive severe atherosclerosis in mice.

The Silent Invasion of the Giants

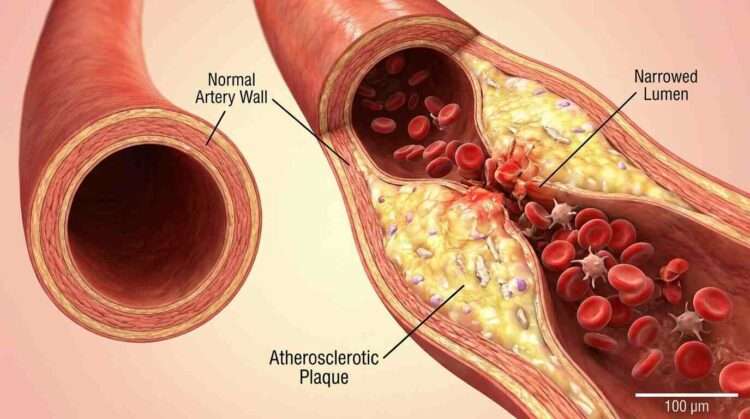

For over half a century, the medical community has operated under a specific set of rules regarding heart disease. We have been told that the villains of vascular health are the small, dense particles—the LDL cholesterol and the “remnants” of broken-down fats that slip through the cracks of our arterial walls like sand through a sieve. The general consensus was that the large, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs), such as chylomicrons formed immediately after a fatty meal, were simply too massive to penetrate the arterial lining. They were viewed as the benign giants of the bloodstream: cumbersome, perhaps, but ultimately too big to fit into the spaces where plaque builds up.

That consensus has just been shattered.

According to a new study published in Nature Communications, researchers have uncovered a startling truth that challenges the foundation of lipid biology. By genetically engineering a unique model to study atherosclerosis in mice, the team led by Dr. Ira J. Goldberg at New York University Grossman School of Medicine has demonstrated that these “giants”—the nascent, intact triglyceride-rich lipoproteins—are not harmless bystanders. They are active, potent drivers of vascular disease, capable of triggering severe inflammation and plaque formation without ever needing to be broken down into remnants first.

The Rabbit Hole of Misunderstanding

To understand why this discovery is so significant, we have to look back at why we thought these particles were safe in the first place. The “remnant hypothesis”—the idea that only partially metabolized fats cause disease—was largely bolstered by studies from the 1980s involving diabetic rabbits. In those older experiments, rabbits fed high-cholesterol diets developed massive lipid particles. Researchers observed that these specific particles did not enter the arterial wall, leading to the widespread conclusion that size was the limiting factor. If a particle is too big, the logic went, it cannot cause atherosclerosis.

However, the new investigation reveals that the scientific community may have been comparing apples to oranges—or rather, mice to diabetic rabbits. The authors of the current study note that the giant particles found in those diabetic rabbits were chemically unusual; they had a lipid composition unlike natural human or mouse chylomicrons and failed to interact with the body’s receptors. They were effectively “ghost” particles, floating by without engaging with the cells.

In contrast, the triglyceride-rich lipoproteins produced by humans after a meal (and by the mice in this study) are biologically active. They don’t just float; they interact. The researchers found that while these large particles might not passively drift through the arterial wall like LDL, they are actively grabbed by receptors on the surface of endothelial cells—the cells lining our blood vessels. This interaction sets off a chain reaction of cellular panic that was previously unrecognized.

Engineering the Perfect Storm

Isolating the specific effects of these large particles has always been a logistical nightmare for scientists. In a normal body, an enzyme called lipoprotein lipase (LpL) acts like a molecular pair of scissors, rapidly chopping up triglycerides into those smaller “remnants.” This rapid conversion makes it nearly impossible to tell if the damage is being done by the original large particle or the leftover pieces.

To solve this, the research team created a biological time capsule. They genetically engineered mice to have an induced whole-body deficiency of lipoprotein lipase (LpL) combined with a deficiency in the LDL receptor (LDLR). This effectively broke the “scissors,” preventing the breakdown of triglycerides, while also removing the primary disposal route for LDL.

The result was a mouse model swimming in intact, unprocessed triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. If the old theories were correct, these mice should have been relatively protected from arterial plaque because their fat particles were “too big” to enter the vessel wall.

Instead, the results were catastrophic for the arteries. The researchers observed that atherosclerosis in mice with this specific genetic profile was significantly more severe than in control groups. The mice developed larger plaques in the aortic root and the brachiocephalic artery—key areas for assessing heart disease risk. The plaques were not just bigger; they were dangerous. They showed signs of instability, filled with inflammatory macrophages and lipids, the very recipe for a heart attack or stroke in humans.

The Cellular Alarm Bells

The most fascinating aspect of this study lies in the “how.” If these particles are too big to squeeze between cells, how are they causing such destruction? The answer lies in cellular communication. The researchers utilized single-cell RNA sequencing to eavesdrop on the conversations happening inside the arterial walls.

What they heard was a scream for help. The endothelial cells, which form the protective barrier of the artery, were not acting as a passive shield. Upon encountering these intact TRLs, the cells began expressing genes associated with high-stress inflammation. Pathways involving MAPK signaling and chemokine signaling—biological “flares” that summon the immune system—were lit up.

The damage wasn’t contained to the surface. The distress signals from the endothelial cells propagated downward to the smooth muscle cells and macrophages (immune cells) residing within the vessel wall. The macrophages, in particular, went into a frenzy, absorbing lipids and transforming into foam cells—the foundational bricks of atherosclerotic plaque.

This suggests that the large fat particles don’t need to physically penetrate deep into the wall to cause damage. By binding to receptors like SR-BI on the surface of the endothelium, they trigger a mechanism known as transcytosis (being transported through the cell) or simply initiate a signaling cascade that degrades the vascular environment. The study proves that “non-remnant TRLs are not benign,” fundamentally altering the narrative that digestion and breakdown are required for toxicity.

Why Your Post-Dinner Blood Work Matters

The implications of this study extend far beyond the laboratory cages. For years, clinical cardiology has focused heavily on fasting lipid profiles—the levels of cholesterol in your blood after you haven’t eaten for 8 to 12 hours. While fasting levels are crucial, they miss a massive part of human existence: the postprandial state.

Most of us spend the majority of our waking lives in a “fed” state. We eat breakfast, and before our triglycerides return to baseline, we eat lunch, and then dinner. This means our arteries are constantly bathed in these nascent, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins.

If the old dogma were true, this post-meal fat spike would be relatively harmless until it was metabolized. But this new data regarding atherosclerosis in mice suggests that the immediate period following a fatty meal is a critical window for vascular injury. The intact chylomicrons circulating right after a burger and fries are capable of initiating inflammation immediately. This aligns with human genetic studies linking mutations in the LpL gene—which slows down the clearing of these fats—to a higher risk of coronary artery disease.

Rethinking Treatment and Prevention

This research paints a complex picture of heart disease that requires a multi-pronged approach. It validates the suspicion that lowering triglycerides is not just about reducing the eventual formation of remnants, but about reducing the burden of the intact particles themselves.

The study also highlights a potential blind spot in current pharmacological strategies. Some treatments focus solely on lowering LDL or clearing remnants. However, if the large, nascent particles are independently atherogenic, therapies need to accelerate the clearance of these particles or block their interaction with the endothelial receptors. The authors note that clinical trials effectively reducing triglycerides have had mixed results in reducing cardiovascular events, perhaps because the intricate dance between particle size, receptor interaction, and inflammation was not fully understood.

Furthermore, this sheds light on the condition known as Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS). Patients with FCS have a genetic inability to break down these large fats. Historically, it was debated whether these patients were at high risk for atherosclerosis because their LDL levels are often low. This study provides the mechanistic proof that despite low LDL, the sheer volume of circulating large fats creates a toxic, inflammatory environment for the arteries.

A New Frontier in Lipidology

We are entering a new era of understanding vascular biology. The “simple” plumbing model—where small particles clog pipes and big ones bounce off—is being replaced by a model of dynamic biological signaling. The artery is a living tissue that reacts, signals, and suffers when exposed to high levels of dietary fats, regardless of the particle size.

According to the authors of the study, “Our data show that intact TRLs contribute to atherosclerosis, explain the association of postprandial lipemia and vascular disease and prove that non-remnant TRLs are not benign.”

As we digest this new information (along with our next meal), the takeaway is clear: biological processes are rarely black and white. What we dismissed as “too big to fail” turned out to be “too big to ignore.” The discovery of how these massive particles drive atherosclerosis in mice serves as a crucial warning for human health, emphasizing that every phase of lipid metabolism—from the moment fat enters the blood—matters for the longevity of our hearts.