New research reveals how Ebola’s matrix protein VP40 hijacks cellular machinery to trigger the deadly inflammatory storms that kill most patients.

The deadliest aspect of Ebola isn’t the virus itself—it’s your own immune system turning against you. Now scientists have identified the molecular trigger behind this self-destruction: a viral protein that silently hijacks cells throughout the body, unleashing an unstoppable wave of inflammation.

The Mystery of Ebola’s Uncontrollable Inflammation

Ebola virus disease remains one of humanity’s most terrifying infections. With case fatality rates reaching 90% in some outbreaks, and the devastating West African epidemic of 2013-2016 claiming over 11,300 lives from more than 28,600 infections, understanding what makes this virus so lethal has been a pressing scientific priority.

For years, researchers have known that what ultimately kills most Ebola patients isn’t the virus directly destroying their organs—it’s a catastrophic immune overreaction known as a cytokine storm. The body floods itself with inflammatory signals, causing blood vessels to leak, organs to fail, and the very immune cells meant to fight the infection to spiral out of control.

But a fundamental question remained unanswered: How exactly does Ebola trigger such an extreme inflammatory response? Previous research pointed to the virus’s surface glycoprotein (GP) activating immune cells through a receptor called TLR4. Yet this explanation had a glaring hole. TLR4 exists only on certain immune cells—macrophages and dendritic cells. If GP and TLR4 were the whole story, blocking this pathway should stop the inflammation. It doesn’t. Mice without TLR4 still die from Ebola infection. Drugs that block TLR4 only partially reduce inflammation in infected animals.

Something else was happening. Something that could ignite inflammation across cell types throughout the body, far beyond the reach of TLR4. Now, an international team of researchers has found it.

The Culprit Hiding in Plain Sight

According to research published in PNAS by Satoko Yamaoka and colleagues at Mayo Clinic, the National Institutes of Health, and the University of Saskatchewan, the real engine of Ebola’s inflammatory devastation is a protein called VP40.

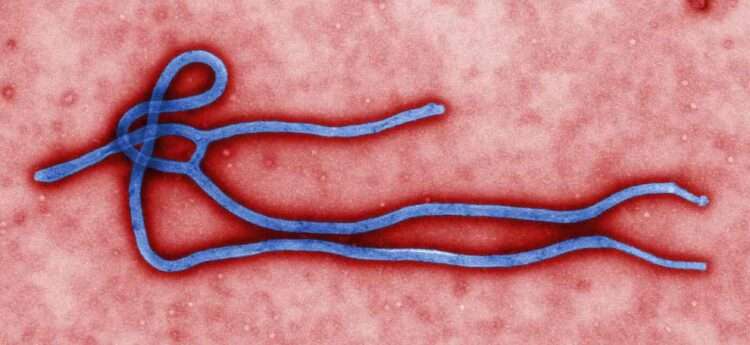

VP40 is Ebola’s matrix protein—a structural component that helps the virus assemble and bud from infected cells. It was already well-studied for its role in viral replication. What nobody fully appreciated until now was its secret second job: triggering sustained, body-wide inflammation through a completely different mechanism than GP.

The research team made their discovery by working backwards from a simple observation. When they infected human cells lacking TLR4 with different species of ebolaviruses, something remarkable happened. Cells infected with the highly lethal Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) produced dramatically higher levels of inflammatory molecules—IL-8, MIP-1β, and TNF-α—compared to cells infected with less virulent species like Bundibugyo virus (BDBV) or the non-lethal Reston virus (RESTV). All three viruses replicated at similar rates. The difference wasn’t in how well they copied themselves—it was in how powerfully they triggered inflammation.

One Protein Among Seven

To identify the viral component responsible, the researchers expressed each of Ebola’s seven structural proteins individually in human cells and measured inflammatory activation. The results were unambiguous: VP40, and only VP40, activated the master inflammatory switch known as NF-κB.

NF-κB is a transcription factor that, when activated, floods into the cell nucleus and turns on hundreds of pro-inflammatory genes. It’s the molecular equivalent of pulling a fire alarm. And VP40 doesn’t just briefly trigger this alarm—it keeps it ringing. While other NF-κB activators typically produce a spike that quickly fades, VP40-induced activation remained elevated for at least 72 hours in laboratory experiments.

The team confirmed this finding across multiple human cell types, including cells derived from the liver (Huh7 and HepG2)—a major target organ during Ebola infection. This wasn’t a quirk of one particular cell line. VP40’s inflammatory power appears to be a general phenomenon.

The Fingerprint of Virulence

Here’s where the story becomes truly compelling. The genus Orthoebolavirus contains six known virus species, each with dramatically different effects on humans. Zaire ebolavirus kills up to 90% of those infected. Sudan virus has roughly 50% fatality. Bundibugyo and Taï Forest viruses are less lethal still. And Reston virus, despite causing fatal disease in monkeys, has never caused confirmed human illness.

When the researchers compared VP40 proteins from these different species, a pattern emerged that mirrors their virulence in humans. VP40 from the deadly Zaire ebolavirus triggered the strongest NF-κB activation. VP40 from the harmless Reston virus barely activated the pathway at all. The moderate killers fell in between.

This correlation suggested something profound: VP40 might be a key determinant of why some ebolaviruses are so much deadlier than others.

24 Amino Acids That Separate Life from Death

To pinpoint exactly what makes Zaire’s VP40 so inflammatory, the team aligned the protein sequences from all six ebolavirus species. Most of the 326-amino-acid protein is highly conserved—nearly identical across species. But one region stood out: a “highly variable region” (HVR) spanning amino acids 21 to 44 at the N-terminus.

The researchers then performed an elegant swap experiment. They created chimeric proteins where Zaire’s VP40 carried the HVR from Bundibugyo or Reston virus, and vice versa. The results were dramatic. Zaire VP40 with a Reston HVR lost most of its inflammatory power. Reston VP40 with a Zaire HVR gained it.

Twenty-four amino acids. That’s what separates a virus that triggers unstoppable inflammation from one that slips by almost unnoticed.

Breaking the Rules of Receptor Signaling

The team then asked: How does VP40 activate NF-κB? The protein isn’t on the cell surface, so it can’t bind external receptors the way GP does with TLR4. Yet somehow it’s triggering a signaling cascade that normally requires receptor activation.

Through careful molecular detective work, the researchers traced VP40’s effects to TNFR1—the tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, a ubiquitous membrane protein present on virtually every cell type in the body. This was puzzling. TNFR1 normally activates only when its ligand, TNFα, binds to it from outside the cell.

But VP40 doesn’t play by those rules. When the team knocked out the gene for TNFα, VP40 still activated NF-κB. When they added antibodies that neutralize TNFα, VP40 still worked. The protein was somehow triggering TNFR1 signaling without the receptor’s normal activating signal—a rare phenomenon called ligand-independent activation.

The researchers speculate that VP40 may achieve this by interacting with the cellular machinery called ESCRT proteins, which regulate how receptors are trafficked within cells. VP40 is known to recruit ESCRT proteins during viral budding. This interaction might inadvertently cluster TNFR1 receptors in ways that trigger signaling. Future research will need to confirm this mechanism.

A Two-Punch Attack

The emerging picture suggests Ebola launches a coordinated two-front assault on the immune system. First, the surface glycoprotein GP triggers temporary inflammation in immune cells through TLR4. Second, VP40 triggers sustained, body-wide inflammation in non-immune cells through TNFR1.

This explains why blocking TLR4 alone doesn’t save infected animals. It also explains how inflammation can spread so far beyond the initial sites of infection. Non-immune cells—hepatocytes, adrenal gland cells, endothelial cells—vastly outnumber immune cells in the body. If VP40 can turn all of them into inflammatory signal factories, the result is the systemic cytokine storm that characterizes fatal Ebola disease.

Toward New Treatments

Understanding VP40’s inflammatory role opens potential new therapeutic avenues. Current Ebola treatments focus on antivirals and supportive care, but targeting the VP40-TNFR1 inflammatory pathway might help dampen the cytokine storm that kills so many patients.

The identification of the HVR as the key inflammatory domain also has implications for vaccine design. VP40 is already being studied as a vaccine antigen alongside GP. Knowing which regions contribute to pathogenicity could help developers create safer, more effective immunogens.

The researchers acknowledge limitations in their study. The experiments were conducted primarily in immortalized cell lines, which don’t perfectly replicate human disease. Confirming these findings in primary cells, organoids, or animal models will be essential next steps.

Still, after decades of Ebola research, scientists now have a clearer picture of the molecular machinery driving one of the virus’s most deadly effects. The protein that builds new viral particles is also, it turns out, the protein that builds the inflammatory fires that consume the host.

Sources:

- Yamaoka, S., et al. (2025). “Ebola virus matrix protein VP40 triggers inflammatory responses linked to the ebolavirus virulence.” PNAS, 123(1), e2508194123. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2508194123

- Jacob, S.T., et al. (2020). “Ebola virus disease.” Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 6, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0147-3

- Liu, T., et al. (2017). “NF-κB signaling in inflammation.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2, 17023. https://doi.org/10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23

- Younan, P., et al. (2017). “The Toll-like receptor 4 antagonist Eritoran protects mice from lethal filovirus challenge.” mBio, 8(2), e00226-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00226-17